On a given week, I find about three or four emails in my inbox asking for advice on training a companion parrot for freeflight. I realize that we have a certain visibility as professional freeflight trainers and frequently post photos and videos of our companion and work parrots enjoying unrestricted outdoor flight that perhaps encourages these queries, but the growing interest is somewhat of a concern. I did not get my start with freeflight as a professional bird trainer, but it was through conscious effort and understanding of the risk of what failure looks like that I met up with the right people when I first started learning about operant conditioning that helped mentor my process in person. I did not learn by email, by internet, by chance, or by a few scattered tips thrown my way. While I know there have been some people who have learned this way, I chose to put the lives of my companions in thoroughly educated hands.

For the purposes of this little article, let’s clarify that freeflight refers specifically to unrestricted outdoor flight. At the beginning of every seminar and workshop we give, we start by saying that though our birds are trained for freeflight, we do not condone freeflight for the average companion parrot owner, we do not think each and every parrot is properly equipped with the skills for this activity, and we do not teach others how to train it. There are too many variables the trainer must have a very comprehensive understanding of, including operant conditioning, before even thinking of taking a parrot to fly outdoors.

That said, there is a growing movement of people that are in fact willing to teach others how to do this with their birds. This practice has been going on for some time. Though I won’t speculate on how successful some of these courses, classes, workshops, or sessions are, I can say that of the most high profile individuals out there that I know of advocating the teaching of freeflight to companion parrots, each has had students with avian casualties related to their programs for a variety of reasons, but the root cause is being ill prepared for freeflight.

Of course, the alternative to people learning it from freeflight trainers is learning how to do so by watching YouTube videos… Talk about being ill prepared! So, what’s the answer

for those who want to learn? The truth is, no matter what, the element of risk is extremely high, particularly in the beginning of a flight training program. And most importantly, freeflight is not simply about teaching your bird to come to your hand when called. There are so many variables out there that a beginning trainer doesn’t even know to be aware of, let alone how to assess their bird’s threshold given its current fitness and skill level. Teaching a flighted recall on cue should be one of many behaviors that the bird and trainer have down fluently, but a strong understanding of body language and the systemic effect positive reinforcement and punishment can have on a relationship is necessary for lasting success and the welfare of a free-flying parrot.

So let’s take a look at a very brief overview of some of the risks associated with freeflight. This is not meant to cover all of the dangers one might encounter, but will give you an idea of the more common factors that free-flying birds might face.

Birds of Prey and other native birds

This is a common one that even the average non-bird person asks me on the beach: “Aren’t you worried about hawks?” The answer is always: Absolutely! Every day for a free flying bird is a new day; just because they went unscathed yesterday does not necessarily lessen the risk for today. Certain times are riskier than others, such as nesting season, which brings about increased territoriality and resource guarding; right after a long rain; and certain bird of prey species are generally more dangerous than others. Similarly, juvenile birds tend to be hungrier (less skilled) and more likely to take risks that adult birds wouldn’t.

In some cases, the devil you do know is not nearly as dangerous as the devil you don’t. The visible hawk is probably just checking out his territory, deciding what to do about these crazy colored, noisy alien intruders. He might decide to give chase, which could lead to exhaustion and your bird could be overtaken or end up somewhere we can’t see them, get to them, or reach them before something dangerous like a dog or car does. Calling your bird out of mid-chase is unlikely and unsafe; he’d have to slow down significantly to land, increasing his risk.

The devil you don’t know is the bird of prey on the hunt. A hawk or falcon can be a crafty predator and ambush their prey, often using visual obstructions to help him sneak up and surprise a single bird (check out Hunting Behavior and Diet of Cooper’s Hawks: An Urban View of the Small-Bird-in-Winter Paradigm, Roth and Lima). Simply put, many people are fooled into a false sense of security scaring away the hawk they saw hanging around. Understanding raptor biology and the birds indigenous to your area is very important.

Other dangers in the skies include birds like crows and ravens and even gulls. These birds are extremely strong flyers (read: chasers!), and a gull could easily chase a bird into the ocean. Corvids are intelligent and might be intrigued by the new kid on the block. Pugnacious passerines such as flycatchers and kingbirds will even fly after parrots and chase them out of sight.

Have I had any encounters? After 13 years, you bet! My birds have been chased by crows, hawks, falcons…. Every time it makes me have to change my pants. It’s always scary. Even our nearly 9 pound Southern Ground Hornbill fears turkey vultures and ravens. And every day has a whole new set of challenges. This is why I only advocate flying more than one bird at a time; flying a single bird creates a huge handicap for that bird. I have seen enough chases to see that not only do parrots help each other out, but they can also prevent the chase from happening. Our parrots are in amazing shape, and that is extremely important to keep them safe, but they are still not as fit as a bird that flies all day for its living. And those birds, even the most fit, get unlucky, too. If predators only relied on the weak and sick for a meal, they’d go hungry a lot. Sometimes, there’s just bad timing.

Neighborhoods

Visibility is a huge issue. Having an open space like a park is important but it doesn’t take much for a miscalculation, and the less skilled bird doesn’t know how to land, panics, and ends up looping out of sight. In fact, that’s how many fly off’s occur: it’s not because birds want to fly away, they just don’t have the skills to come back or land where they want to. But I digress. There are more problems in neighborhoods: dogs, pools, and cars. I know of casualties due to all of the above. A panicked bird can fly a long ways at first, but exhaustion takes over quickly, and they will land very abruptly. I know of a few very competent flying parrots lost to cars on slow country roads, not because the birds were panicked but because the birds ranged too far and simply did not understand the danger of a moving car.

The danger of power lines, whether it’s from running into them or through electrocution, cannot be stressed enough. Windows on homes and buildings are just as dangerous from the outside as they are from the inside.

Neighbors themselves can be a danger. If they find your bird a nuisance (and typically, outdoor birds are more pesky than birds safely tucked away in living rooms), this can make for trouble. Sadly, there are more than a couple firsthand accounts of neighbors poisoning or shooting free-flying parrots when the offending party had no idea there was ever even an issue. Hungry and thirsty lost birds looking for safety will befriend strangers and might find themselves a new home.

Training

As I had mentioned before, training a bird for freeflight is not just about teaching it to fly

to the hand on cue. While this basic behavior is extremely important and it should be the most fluent thing that your bird does, you as a trainer need to be acutely aware of every interaction you have with your bird, indoors and out. Have you ever trained your parrot to do anything with positive reinforcement? Is there any behavior cue your bird will respond to 100% of the time, no matter what?

The systemic effect of operant conditioning means each interaction we have with our parrots gives them more information about how to act in the future. A parrot that is given

the choice to step on to our hand or fly off of our hand to someone else or another perch, after which that behavior is reinforced with a lovely bit of nut or other treat will have strong positive associations with these behaviors. One that is forced to step up by pressing on his lower abdomen until he has no choice but to step up or has his toes plucked up and perhaps tossed off the hand in order to get to fly to another perch will have negative associations with these behaviors, and we will see an overall avoidance in that bird wishing to engage with us. A bird that is tricked into behaviors by having that ever increasing distance to get to a treat will stop trusting the treat. A free-flighted bird must find it valuable to engage with you in all times. He must know that if he flies down from a tree, he is not going to get shoved into a crate to go home, or he will stay up in that tree.

Recognizing body language is another very important part of flight training. A bird that is nervous about being outside will not be as successful and not find it pleasurable to be out there. A bird that doesn’t feel like going out is also important to recognize and respond appropriately to. Taking a flier out on a

less than optimum day leaves the bird more vulnerable to attack and puts them under greater physiological stress. Sensitivity to body language becomes paramount as a freeflight trainer in order to keep your cues strong, predict your bird’s fitness given a specific situation, and reduce stress for you and your parrot. Unskilled trainers can unwittingly train latency or rely too heavily on weight management to train the behaviors that they want without an experienced eye on the consequences they are producing.

Overall, the amount of time put in to having a free-flying parrot is tremendous. Ask any falconer and they will tell you that the time commitment is more than just an average hobby. It’s not just a cool past-time. There is much to be done even on off-days to keep your bird’s cues strong, and you must be flying your birds often to keep their fitness at a responsible level necessary for encountering outdoor elements. To take this activity on with the passivity of having your dog off-leash at the dog park is not giving your bird’s life the proper respect it deserves.

A flight session, especially in early training, can last a few minutes or it can last an entire

day when the unexpected problem arises, which can be challenging for the average schedule. While it’s good to teach birds to come out of high places indoors first in areas such as hangars or warehouses, nothing can replicate an 80 foot tree with obstructing branches and unstable take-off perches of which new fliers will inevitably find themselves at the very top as well as very deep in the middle. Coming out of those is all part of the learning process, and every individual learns at a different rate, no matter how motivated they are by fear, hunger, or bond with their human. There are so many variables to consider in these situations.

Sexual Maturity

Some advocates of free flight have flown their birds successfully for a few years but have not yet met with the trials and tribulations of flying sexually mature birds. These birds may develop strong relationships with other members of the flock, which can cause problems not only in nest seeking behavior but also put other birds in danger. Even the single flying bird (again, not something I recommend) or birds flown only in same-sex flocks can show a strong drive to find a nest. In the controlled indoor environment, we can much more easily limit their access to nesting opportunities. Outdoors, we do not have such control. I have seen an eclectus female disappear in the middle of a wide open prairie, only to be found by chance in a prairie dog burrow. Some trainers have to keep their birds grounded, so to speak, for a few months out of the year because the urge to find nesting opportunities is so strong that they have ended up down chimneys or causing problems for the neighbors. Sex is a powerful motivator, especially when birds do not otherwise have access to sexual stimulation. Deterring a bird from a nice dark closet is hard enough inside, but there is real danger when there is a nest space worth defending outdoors.

Stressss face! Greenwing macaw Luca finally learned to come out of a tree during an early training flight.

Last Wild Cards

There are a few other aspects of teaching a parrot to fly free that I occasionally get asked about.

- Should I lightly clip my parrot’s wings when I first start so that they can’t fly too far?

The answer is a resounding NO! First, if your bird flies too far, then you are doing it wrong. You have asked too much too soon or you have misjudged your environmental variables, thus putting your bird in a situation that it does not have the skills, education, or appropriate environment for. Second, clipping your bird puts a handicap on it. It reduces the surface area of the wing, which is necessary for maneuvering, slowing down, flying downward, and landing. It also puts your bird at a huge disadvantage if it were to get chased by another bird or if lost steam and landed in a compromising location. Clipping gives the owner a dangerously false sense of security.

- Should I buy an unweaned baby to train it for freeflight?

There has been much debate about this practice, and quite frankly, I have seen firsthand the physiological and psychological effects of amateurs buying an unweaned baby birds that I feel very strongly against this practice for a variety of reasons. Nor do I think it is necessary. While I do believe that it is important to realize that not every bird is suited for

Military Macaw Indy came to us after being completely weaned and did not start free flight training for a couple of months after weaning because we were on location in Brazil. Nothing stops her in the air.

freeflight, and many people want to take the bird that they have and give it unrestricted outdoor flight, acquiring young birds with individual characteristics well suited for this type of training is far more valuable than buying an unweaned baby bird. An experienced trainer knows what to look for, will tell you that not every bird has these characteristics, and even early training cannot necessarily override individual strengths and weaknesses. Of the dozens of birds that I have trained, only a few of them were unweaned and there is absolutely no difference in their competency or ease in training as the others. Some feel that the use of unweaned birds helps because the trainer can rely on the bond between perceived parent and chick. However, it is my belief that relying on this bond, this window of opportunity, is not necessary and could instead encourage the trainer to adhere to more lenient standards of latency and stimulus control, which would not serve the bird’s safety well going into the future. For more on this subject, Good Bird Inc’s Barbara Heidenreich wrote this: http://carlylusflightblog.com/2008/06/cross-post-barbara-heidenreich-on-weaning-baby-bond/ and parrot breeder and trainer Wendy Craig also wrote this one: http://carlylusflightblog.com/2008/06/buying-unweaned-baby-birds/.

That said, I would never advocate the training of an older bird for free flight in a professional or amateur setting. Younger birds that are at their natural experimental, devil-may-care fledging period are actually much safer than older birds because they are more willing to try to do crazy things like bomb out of tree despite bonking their wings and tail on branches, where an older bird might be more fussy. Nature is telling them to try new things. Much like learning a new language as an adult is more challenging, older birds learning to free fly will be more likely to “fly with an accent,” which will make them more susceptible to the specialized vision of a bird of prey and they could perhaps be more reluctant to get themselves out of a pickle.

3. What about using a harness?

Using a harness to take a fully flighted bird outside and allow it flight can be extremely dangerous and potentially relationship damaging. The leash can easily get tangled in wings, branches, and any overhead objects, potentially ending in death for your bird if it hangs in a way that it cannot be freed. Further, as quality falconers know, continually having to check your with the harness and lead as a training tool for going too far or the wrong direction falls in the punishment quadrant of operant conditioning and can lead to fallout behaviors such as mistrust of the harness itself, leading to further breakdown of behavior. Teaching your bird to wear the harness for the purpose of taking it outside safely without flight is completely different, as it does not involve the risks that harness flight does.

It cannot be said enough: freeflying your parrot is not simply about training excellent recall. It is not about having an open space to fly in without trees and excellent visibility. It is not about having an environment without birds of prey. These conditions simply do not exist on a consistent basis. Freeflight is not about giving your best feathered buddy the ultimate gift. It is not about pride in one’s training capabilities; some of the best trainers I know recognize they do not have the right conditions and resources to fly their birds. And perhaps one thing that professional trainers are always aware of that not all companion parrot owners aren’t is that risks can be mitigated but never extinguished. Losses can occur no matter how good of trainers we are. We can’t control all of the variables all of the time, but experience does tell us how to be as successful as possible.

What can you do if you want to see your bird fly but aren’t prepared for the commitment of free flight? There are still ways that you can enhance both you and your bird’s life. As I just mentioned, learn all that you can about behavior from qualified sources! Positive

reinforcement is such a powerful tool with far-reaching effects. Build an aviary as big as you can possibly make it! Enrich your birds’ lives in other ways. Visit wild parrots and support sustainable, responsible ecotourism (Yes! This does make a difference in keeping wild parrots flying free!). Learn how to train birds to live safely and responsibly in the home with their wings intact. Yes, it does take extra work and education, but the rewards are exponentially greater for everyone.

I strongly encourage all who are interested in this subject to do as much research as

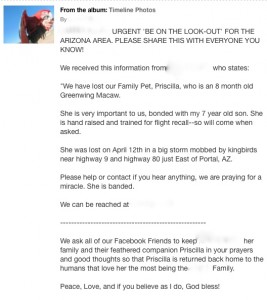

Fly away companion parrot free flight notice on social media. The risks are plentiful, particularly with inexperienced birds and trainers (no shaming intended, just observations from my own experience).

possible before embarking on this path. Become a behavior nerd! There is so much to learn, and it requires a huge commitment of time and energy. Attend workshops, clinics, seminars, and conferences with respectable, experienced trainers. Know your teachers! A picture may be worth a thousand words, but it is only a moment in time. The successes show up all over on Facebook and YouTube, but we don’t often hear about the failures due to embarrassment and grief. Trust me, they are out there. I certainly understand why people fear being tarred and feathered, and I don’t mean to shame anyone for their losses, only to help this from happening to other birds. I leave on this note: a very brave person posted his journey on YouTube. I hope you watch it.

http://avianambassadors.com/BirdTraining/comments-on-youtube-video/

Yours in educated actions,

hh